My guest today is Corinne Hoebers, author of Tethered Spirits which was published by OC Publishing in October 2025 and is available to purchase in paperbook or as an ebook.

You can read an excerpt from Tethered Spirits below.

About the Book

Against the violent backdrop of the French and Indian (Seven Years) War, two German siblings come to learn about and understand the Mi’kmaq.

Christian, now named Bear Cub, lives with the ancient People and develops a deep bond with his chosen brother, Eagle Feather, while his new family’s way of life is increasingly threatened. On the outskirts of Lunenburg, Hanna, his younger sister, befriends a Mi’kmaw Elder and questions her papa’s ownership of the land they are settling.

Christian immerses himself in the Mi’kmaw language and the ways of the land, prepared to defend the People alongside Eagle Feather. Christian’s father and older sister, Elisabeth, refuse to accept his new way of life; nor will they recognize the humanity of their perceived enemy. Christian is caught between two diverse families and cultures—the one to which he was born and to whom he feels obligated, and the one he has grown to love and respect.

Settlers and Mi’kmaq alike struggle on land that is the ancestral home to one and promised to the other, a struggle that resonates to this day.

Find Tethered Spirits on Goodreads

Excerpt from Tethered Spirits by Corinne Hoebers

Bear Cub. Like a duck to water, he naturally slipped into his new name. Christian sounded foreign to him now. He looked skyward to where Eagle Feather was pointing, and they watched the eagle slowly drift above the forest canopy before landing at the topmost part of a spruce tree. As his large, graceful wings collapsed around his body, he cocked his white head and looked down upon them. Then, this lofty creature, Kitpu, the messenger of prayers to the Spirit World, who soars closest to Kisu’lkw, the breath of creation, effortlessly lifted upward in flight. Bear Cub grinned at his brother as they too moved on.

Bear Cub now lived a life very different from the one to which he was born. He understood that in this circle of life, no living being had dominion over the other. The People addressed flora and fauna as people—non-human people. They asked flora for permission before harvesting and demonstrated their gratitude by minimizing harm. An Elder had taught Bear Cub about the practice of Netukulimk—take only what you need. If over-harvested, the plants and animals would leave. The Mi’kmaq survived by watching and listening to the world around them.

When he was seventeen years old, he had paddled from Dartmouth in search of his brother Jakob when their mother lay dying. Eagle Feather found Bear Cub alone and near death. Living with the Mi’kmaq, Bear Cub had easily adjusted to their beliefs; but a battle raged within him on whether or not to return to his birth family. Could he, after all this time?

Then there was Papa. Bear Cub pushed him to a dark corner of his mind and inhaled deeply to suppress the image of his biological father. The musty scent of decay in the forest breathed renewed creation. With each step, his feet sank deep into the living moss. Bear Cub relaxed. As in the old times, the rich undergrowth of the forest sustained the Mi’kmaq. Rain droplets dotted the toes of moccasin flowers—their roots a medicine used to treat headaches and fevers. Bunchberries, their tiny white flowers sprinkled amid the ferns, were medicine for the stomach.

Once again, Papa entered his thoughts unannounced. Bear Cub’s body tightened. His father had forced him to become an apprentice to his uncle, to learn the weaving business. But Bear Cub could never trade the farmland soil he loved to sift through his fingers for the coarse wool and rigid pedals of the loom. His uncle taught him with the sting of his belt. As the memory festered, Bear Cub’s temples throbbed. Papa had ignored his needs. Did he want to return?

Eagle Feather waved his hand at his brother. Bear Cub had not noticed they had arrived at the second weir below the river’s tide head. Slipping the heavy basket of mackerel and eels from his sweaty back, Bear Cub plunged into the cold water. His exhausting internal battle washed away. He now observed this V-shaped weir, pointed downstream. Alongside his Mi’kmaw brothers, he had learned to build it from piled stones and hemlock boughs. It was holding up well. The large net at the apex must be full by now, he thought.

He could feel the smooth skin of the fish churning about his feet. Plamu’k, he said to himself, the Mi’kmaw name for these delicacies. Eagle Feather clutched the silver-coloured smolts in both hands while Bear Cub stitched a spruce root through the lower part of each mouth. One by one they were securely tied and bundled onto the spear. The women of the village had recently boiled spruce roots, splitting them to be used for baskets and canoes. Eagle Feather had snuck a few for this purpose, hoping his mother would not notice.

Once they had stitched the last of the fish, Eagle Feather tossed the bundles onto the bank of the river, then walked farther upstream to a deeper section. Bear Cub ran after him. When he waded into the water’s depth, Bear Cub attempted to stab a salmon with his three-pronged spear. His brother laughed at his clumsiness and pushed him under. Bear Cub bounced up to the surface, gasping for air.

“I would starve waiting for you to catch food,” Eagle Feather teased.

Bear Cub grabbed a handful of his brother’s black hair, dragging him under. But his brother escaped his grip, reappearing at the shoreline.

“I’m as good as my teacher,” Bear Cub called back.

“Come, my brother,” Eagle Feather called. “It is time to return to camp.”

Bear Cub waded back. “Leave it to you to quit when I was winning.” He slapped his brother on the back.

He could feel the smooth skin of the fish churning about his feet.

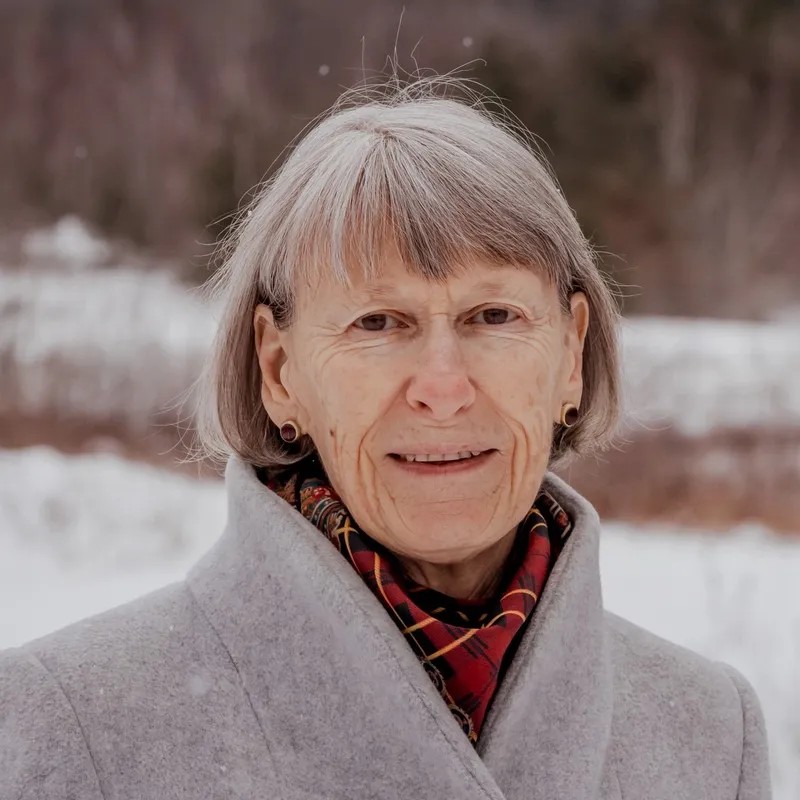

About the Author

After twenty-five years of adventures in Toronto and Calgary and a forty-year career in the travel industry, Corinne felt the pull to return to Nova Scotia, where she grew up. As a direct descendant of one of the first 1753 settlers of Lunenburg, her passion for history moved her to write her first self-published novel, Call of a Distant Shore, which won the Silver Medal for Canada East, Best Fiction 2009, from the Independent Publisher Book Awards. Soon after, she began a comprehensive journey that led her to write Tethered Spirits.

Corinne loves the mysterious, mystical, and diverse world we live in and believes that just because we cannot see it does not mean it does not exist—it simply has not been discovered yet. She is an anomaly who does not own a microwave, dishwasher, or cellphone. Her life encompasses lively games with her bridge friends; her love of gardening where things grow, buzz, and crawl, with a visit most mornings from her helper, the neighbour cat; practising Tai Chi; and hiking with her husband through hemlock forests and unspoiled nature trails in out-of- the-way places.

A member of the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia, Corinne lives in the Annapolis Valley with her Dutch husband and a British Blue cat named Toby who is happiest when he is fed, loved, and has a clean litter box and a warm lap. Corinne and her husband have four grandchildren. (Photo/bio: Publisher website)

I enjoyed the excerpt and the synopsis sounds good. My daughter lives in Nova Scotia, and I know the Mi’kmaw is the second official language. I am adding this book to my TBR shelf, as well as a possible read for the Great Canadian Reading Challenge.

LikeLike

Oh that’s great. I’m glad it’s put it on your radar.

LikeLiked by 1 person