I’m delighted to be hosting today’s stop on the blog tour for The Coven by Graham Masterton, a historical mystery set in 18th century London. The Coven is the second book in the Beatrice Scarlet series and the follow-up to Scarlet Widow. I’m thrilled that Graham has agreed to answer some questions about The Coven and how he goes about researching his novels.

About the Book

About the Book

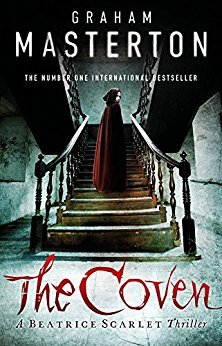

They say the girls were witches. But Beatrice Scarlet, the apothecary’s daughter, is sure they were innocent victims… London, 1758: Beatrice Scarlet, the apothecary’s daughter, has found a position at St Mary Magdalene’s Refuge for fallen women. She enjoys the work and soon forms a close bond with her charges. The refuge is supported by a wealthy tobacco merchant, who regularly offers the girls steady work to aid their rehabilitation. But when seven girls sent to his factory disappear, Beatrice is uneasy. Their would-be benefactor claims they were a coven of witches, beholden only to Satan and his demonic misdeeds. But Beatrice is convinced something much darker than witchcraft is at play…

Format: eBook (368 pp.), Hardcover (416 pp.) Publisher: Head of Zeus

Published: 5th October 2017 Genre: Historical Mystery

Purchase Links*

Amazon.co.uk ǀ Amazon.com

*links provided for convenience, not as part of any affiliate programme

Find The Coven on Goodreads

Interview with Graham Masterton, author of The Coven

Without giving too much away, can you tell us a bit about The Coven?

Beatrice Scarlet is the daughter of an inspirational London apothecary, who taught her everything he knew about chemicals and cures. She emigrated to America with her husband, a non-conformist parson, but after his tragic death she has to return to London, where the church have offered her a position at a home for reforming young prostitutes. The home is mainly financed by a tobacco baron, George Hazzard, who regularly picks out girls to work at his factory in Hackney stripping tobacco leaves and rolling cigars. However the latest seven girls that he has recruited go missing, and when Beatrice tries to find out where they might have gone, George Hazzard shows her evidence that they must have formed a coven and summoned Satan, and escaped from the factory by using dark magic. Beatrice is sceptical about this, and tries to find forensic evidence to show what really happened to them. Eventually her chemical research reveals the truth, and it is far more horrific than anything the Devil could have devised. It plunges Beatrice into the sordid depths of 18th century London, with all its dirt and disease and poverty and sexual exploitation, and puts both Beatrice and her young daughter into terrible jeopardy.

The Coven is the second book in your Beatrice Scarlet series. What are the challenges of writing a series compared to a standalone novel?

Remembering who all the characters are and what they did in the first novel is quite a challenge, especially if you have written other novels in between. For me, the most important consideration is to make sure that the characters develop emotionally, and that they learn by their experiences. No matter how outlandish some of my plots maybe, I try to make my characters and their situations as real and as vivid as possible, and particularly when I am writing about female characters, I am extremely sensitive to the social mores of the age and what was expected (and demanded) of women in whatever age the novel is set. What I do like about a series, though, is that you can leave a few cliff-hangers at the end.

When you conceived the idea for the Beatrice Scarlet series, what made you choose the 1750s as the time period in which to set the books?

Most importantly, it was a time when breakthroughs were beginning to be made in science and medicine, so there was an intriguing clash between old-school apothecaries and more progressive chemists like Beatrice’s father. Some of the traditional treatments were bizarre, like taking mercury to cure venereal disease, which made the patient’s teeth fall out and eventually killed them. Also it was the early days of American colonization, with its fervent religious drive, and in Scarlet Widow I wanted to show how religious zealotry conflicted with scientific fact. Apart from that, I was fascinated by the costumes and the language and by the challenge of writing a crime thriller in which nobody has a mobile phone or a car. You want to get to the scene of the crime quickly? Call for a hackney carriage, or run.

How do you approach the research for your books? Do you enjoy the process of research?

I relish the research, but it does make the process of writing a novel very slow. You have to check if every word was in usage at the time. Was ‘flabbergasted’ known in 1758? Answer – yes. But when a hackney driver suggests to Beatrice that London is so smelly that she will need a clothes-peg on her nose…no, sorry. Clothes-pegs weren’t invented until the 1820s by the Puritans in Boston. Before that, washing was hung out to dry on bushes in the summer or on fireguards in the winter, which led to a great many house fires in London. Did women wear knickers? What kind of street-lighting was there, if any? What time did people have breakfast, and what did they eat? How much did it cost to take a hackney from St Paul’s Cathedral to Bow Street? (About 1s 6d.) Thank the Lord for Google, but I also found an incredible book by Professor Jerry White about London in the 18th century and it contains almost every conceivable fact you would ever want to know about living in the capital in that era. Even a whole lot of facts you didn’t want to know.

On behalf of squeamish readers, will they need to leave the light on or check under the bed after reading The Coven?

All of my novels in their different ways are confrontational, in that I believe in facing up to the realities of life, as well as trying to be entertaining. There are some extreme moments in The Coven, although nothing worse than actually happened in 18th century London. As far as supernatural terror is concerned, it really depends on how superstitious you are, and whether you would be frightened by the sound of somebody or something clawing frantically at your bedroom door in the middle of the night.

You’ve written over one hundred novels. Do you still get the same feeling of excitement when you sit down to start a new one?

Yes, I love it. I love meeting the characters. I love describing new places. I love the way that I suddenly discover the relevance of events that I wrote about in the opening scenes of a novel, even though they seemed random at the time. In some ways it’s like being a clockmaker. You start off with a workbench scattered with scores of cogs and springs and levers and end up with a ticking timepiece. What is also exciting (if a little hair-raising) is that much of what I write about in my novels has a way of coming true. In my latest crime thriller Dead Girls Dancing, a dance studio overlooking the River Lee in Cork burns down after an arson attack. A week after the book was published, a building on the same side of the river less than half a mile away was burned down. In the same book, the leader of an IRA splinter group gets shot, and less than a week after I had written that, the former leader of an IRA gang was shot only two streets away from my fictitious shooting. Some people say that my 1980s horror novel The Hell Candidate in which a presidential hopeful is possessed by the Devil and wins the US election was predictive, but I couldn’t possibly comment about that.

Do you have a special place to write or any writing rituals?

My desk faces the window which overlooks the street where I live, because I am extremely nosy and like to see what the neighbours are up to. I have a photograph next to my computer of my late wife Wiescka smiling at me in encouragement, as she always did. I start writing about 9am with a mug of horseshoe coffee, so called because the American railroad workers said it was so strong you could float a horseshoe in it. I don’t listen to music while I write because I feel that it would affect the rhythm of what I am putting down on the page. I usually take a break around midday to stretch my legs and buy a newspaper then it’s back to work until 4pm or 5pm. After that I might slope off to the pub to meet some friends or take a pretty young woman out to dinner.

Although you’re probably best known for your horror books, you’ve published books in a wide range of genres. Is there a genre you’d still like to experiment with?

When I started writing novels, I didn’t know what a ‘genre’ was. In reality it’s a classification invented by WH Smith and other trade booksellers to save them the bother of reading books to find out what they’re about before they put them on their shelves for sale. I made a career mistake in some ways when I stopped writing horror for a year or two after The Manitou and The Djinn and Charnel House and tried my hand at historical sagas like Rich and Railroad and Maiden Voyage. The Manitou and Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot were published around the same time and it’s likely that if I had stuck with horror I could have continued steadily to build up my audience like he did. But I have no regrets. I have enjoyed every minute of writing. I can’t think of any particular genre I would like to experiment with, although I would like to go back to writing humour. I began a humorous novel about a country-and-western group called If Pigs Could Sing (you can check it out in the Fiction section of my website) but my then agent hated it and so I abandoned it.

How do you think you would have coped living in 18th century England?

Probably very badly. I am quite fastidious and the thought of never brushing my teeth and wiping my sticky hands on my jacket while I am having dinner and having to endure the loud and unashamed farts of other people in public…I don’t think I could take it. There were 65,000 prostitutes in London in the late 1750s and sex was readily available almost anywhere for a shilling or two (James Boswell had it under Westminster Bridge). The trouble was, most of the girls carried some kind of STD and you would be lucky not to end up with gonorrhoea or syphilis. Cholera and smallpox and typhus were rife, and you would be lucky to live until you were 33.

Will there be further adventures for Beatrice Scarlet?

Highly likely!

Thank you, Graham, for those fascinating answers. I’m sure fans of historical mysteries are going to love getting to know Beatrice Scarlet in Scarlet Widow and The Coven and, from the sound of it, in future books.

About the Author

About the Author

Graham Masterton was born in Edinburgh in 1946. His grandfather was Thomas Thorne Baker, the eminent scientist who invented DayGlo and was the first man to transmit news photographs by wireless. After training as a newspaper reporter, Graham went on to edit the new British men’s magazine Mayfair, where he encouraged William Burroughs to develop a series of scientific and philosophical articles which eventually became Burroughs’ novel The Wild Boys. At the age of 24, Graham was appointed executive editor of both Penthouse and Penthouse Forum magazines.

Graham Masterton’s debut as a horror author began with The Manitou in 1976, a chilling tale of a Native American medicine man reborn in the present day to exact his revenge on the white man. It became an instant bestseller and was filmed with Tony Curtis, Susan Strasberg, Burgess Meredith, Michael Ansara, Stella Stevens and Ann Sothern. Altogether Graham has written more than a hundred novels ranging from thrillers (The Sweetman Curve, Ikon) to disaster novels (Plague, Famine) to historical sagas (Rich and Maiden Voyage – both appeared in the New York Times bestseller list). He has published four collections of short stories, Fortnight of Fear, Flights of Fear, Faces of Fear and Feelings of Fear.

He has also written horror novels for children (House of Bones, Hair-Raiser) and has just finished the fifth volume in a very popular series for young adults, Rook, based on the adventures of an idiosyncratic remedial English teacher in a Los Angeles community college who has the facility to see ghosts. Since then Graham has published more than 35 horror novels, including Charnel House, which was awarded a Special Edgar by Mystery Writers of America; Mirror, which was awarded a Silver Medal by West Coast Review of Books; and Family Portrait, an update of Oscar Wilde’s tale, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which was the only non-French winner of the prestigious Prix Julia Verlanger in France.

He lives in a Gothic Victorian mansion high above the River Lee in Cork, Ireland.

Connect with Graham