About the Book

About the Book

Set during World War I on an isolated country estate just outside London, Rebecca West’s haunting novel The Return of the Soldier follows Chris Baldry, a shell-shocked captain suffering from amnesia, as he makes a bittersweet homecoming to the three women who have helped shape his life. Will the devoted wife he can no longer recollect, the favourite cousin he remembers only as a childhood friend, and the poor innkeeper’s daughter he once courted leave Chris to languish in a safe, dreamy past—or will they help him recover his memory so that he can return to the front? The answer is revealed through a heart wrenching, unexpected sacrifice.

| Format: | ebook | Publisher: | Xist Publishing | Pages: | 70 |

| Publication: | 14th March 2016 | Genre: | Literary Fiction |

Purchase Links*

Amazon.co.uk ǀ

*links provided for convenience, not as part of any affiliate programme

Find The Return of the Soldier on Goodreads

My Review

The Return of the Soldier is one of the books that makes up my Classics Club Challenge. The challenge has been rather neglected of late so I was pleased to be able to make room in my reading schedule for this book, helped by the fact it is a slim volume.

Chris Baldry’s return from the war is awaited by his wife, Kitty and his cousin, Jenny, who is the narrator of the story. Kitty’s and Jenny’s lives both seem to revolve around Chris. Their role is to supply his (perceived) needs. Indeed there is a sense that their desire for his return is partly so that everything can return to the way it was before he went away. Kitty is in a kind of stasis following the death of their son five years earlier and Jenny seems unsure of her role in the absence of her childhood friend and cousin.

From the reader’s perspective it seems a vain hope that anyone could be unchanged by the experience of war and indeed, when Chris does return, it’s not in the manner Kitty and Jenny hoped and it’s clear everything will not go back to how it was before. Their dreams of Chris’s return are shattered by the arrival of Margaret Grey who was involved with Chris many years before. She brings news that he has been wounded, not physically but psychologically. A severe case of amnesia means he has forgotten everything about the past fifteen years. When he returns home, he has no memory of his wife or his son. Heartbreakingly for Kitty, it is Margaret to whom Chris now gives his affections, picking up their relationship as if the events of the intervening years (and her marriage to someone else) had never taken place.

At this point, I’m going to be honest and say that, although the writing is fantastic, this book was hard going because I found most of the characters very unlikeable. There was a tone of class snobbery from, in particular, the narrator and Kitty towards Margaret that I found quite unpleasant. For example, this description of Mrs Grey’s arrival with the news:

‘She was repulsively furred with neglect and poverty, as even a good glove that has dropped down behind a bed in a hotel and has lain undisturbed for a day or two is repulsive when the chambermaid retrieves it from the dust and fluff.’

The snobbery isn’t confined to Mrs Grey’s appearance either but to her intellect as well.

‘She answered with an odd glibness and humility, as though tendering us a term she had long brooded over without arriving at comprehension, and hoping that our superior intelligences would make something of it.’

And I wasn’t convinced that the author was seeking to satirise their snobbery.

Although understandably affected by the death of her child, I still found Kitty a distinctly unsympathetic character. Her air of self-pity was unattractive and it seemed part of her outrage at the situation was that Chris’s affections were now directed towards a woman of lower social status.

Margaret comes across as the most likeable character. Despite a difficult marriage, she is a loyal and devoted wife and she is the person who wants the best for Chris even if that means she will lose him again. Towards the end of the novel, I grew to like Jenny a little more because it does seem she is able to place Chris’s interests at the forefront and she comes to realise that Chris needs more than mere physical comforts.

‘It had been our pretence that by wearing costly clothes and organizing a costly life we had been servants of his desire. But [Margaret] revealed the truth that, although he did indeed desire a magnificent house, it was a house not built with hands.’

The Return of the Soldier represents an early exploration of the psychological effects of war (what we would understand as shell-shock, although this term is not used). Chris’s disorientation when he returns home – he goes towards the wrong bedroom, trips over steps that he doesn’t remember being there – and the effect this has on the rest of the household is vividly evoked: ‘Strangeness has come into the house, and everything was appalled by it, even time.’

Chris’s loss of memory exposes the emptiness of Kitty’s and Jenny’s existence without him.

‘But by the blankness of those eyes which saw me only as a disregarded playmate and Kitty not at all save as a stranger who had somehow become a decorative presence in his home and the orderer of his meals he let us know completely where we were.’

More than anything the book explores the moral dilemma of what is the right thing to do if all options have undesirable consequences.

In three words: Intimate, thought-provoking, challenging

Try something similar…The Voyage Out by Virginia Woolf

About the Author

About the Author

Cicely Isabel Fairfield, known by her pen name Rebecca West was an English author, journalist, literary critic and travel writer. A prolific, protean author who wrote in many genres, West was committed to feminist and liberal principles and was one of the foremost public intellectuals of the twentieth century. She reviewed books for The Times, the New York Herald Tribune, the Sunday Telegraph, and the New Republic, and she was a correspondent for The Bookman. Her major works include Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), on the history and culture of Yugoslavia; A Train of Powder (1955), her coverage of the Nuremberg trials, published originally in The New Yorker; The Meaning of Treason, later The New Meaning of Treason, a study of World War II and Communist traitors; The Return of the Soldier, a modernist World War I novel; and the “Aubrey trilogy” of autobiographical novels, The Fountain Overflows, This Real Night, and Cousin Rosamund. Time called her “indisputably the world’s number one woman writer” in 1947. She was made CBE in 1949 and DBE in 1959, in recognition of her outstanding contributions to British letters.

About the Book

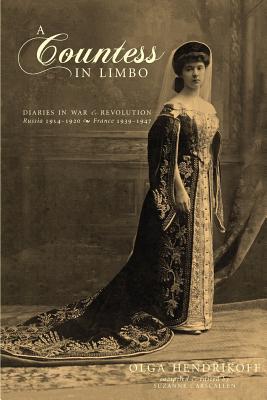

About the Book Sue Carscallen spent 20 years with Olga Hendrikoff before her great aunt’s passing in 1987. Carscallen stumbled upon Hendrikoff’s diaries hidden in a trunk at her great aunt’s Calgary home. Over time she unraveled the mysteries hidden in the manuscripts, traveling to France and Russia to supplement her research into Hendrikoff’s life. Today, Carscallen resides in Calgary.

Sue Carscallen spent 20 years with Olga Hendrikoff before her great aunt’s passing in 1987. Carscallen stumbled upon Hendrikoff’s diaries hidden in a trunk at her great aunt’s Calgary home. Over time she unraveled the mysteries hidden in the manuscripts, traveling to France and Russia to supplement her research into Hendrikoff’s life. Today, Carscallen resides in Calgary.