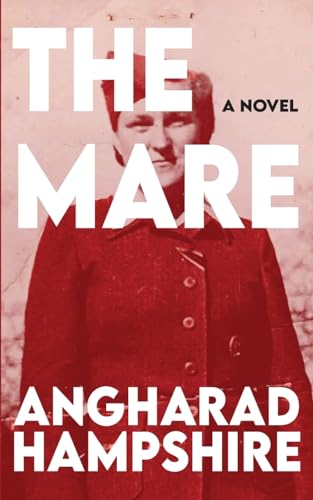

About the Book

Hermine Braunsteiner was the first person to be extradited from the Unites States for Nazi war crimes. Hermine was one of a few thousand women to work as a female concentration camp guard. Prisoners nicknamed her ‘the Mare’ because she kicked people to death. When the camps were liberated, Hermine escaped and fled back to Vienna.

Many years later, she met Russell Ryan, an American man holidaying in Austria. They fell in love, married, and moved to New York, where she lived a quiet life as an adoring suburban housewife, beloved friend and neighbour. No-one, not even her husband, knew the truth of her past, until one day a New York Times journalist knocked on their door, blowing their lives apart.

The Mare tells Hermine and Russell’s story for the first time in fiction. It explores how an ordinary woman could descend so quickly into evil, examining the role played by government propaganda, ideology, fear and cognitive dissonance, and asks why her husband chose to stay with her despite discovering what she had done.

Format: Paperback (320 pages) Publisher: Northodox Press

Publication date: 19th September 2024 Genre: Historical Fiction

Find The Mare on Goodreads

Purchase The Mare from Bookshop.org [Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops]

My Review

Given its subject matter, The Mare is a book I may not have chosen to read had it not been shortlisted for this year’s Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. How glad I am that I did though because, for me, it was the most impressive book on the shortlist. I even tipped it as the winner although, in the end, it lost out to Andrew Miller’s The Land in Winter (also a terrific book).

The Mare is the fictionalised account of the life of Hermine Braunsteiner who served as a prison guard in two concentration camps during WW2. It alternates between the points of view of Hermine herself and her husband, Russell Ryan. Each gives us a very different impression.

Russell meets Hermine in 1957 at a hotel in Austria where she is working. From the very beginning, he is besotted with her. She takes the driving seat in their relationship, whether due to genuine affection for him or because he offers a convenient gateway to a better life. He navigates the complex process of obtaining a marriage licence and facilitating their move to America. Their conventional married life is upended in July 1964 when they are confronted by allegations about Hermine’s past. Russell is unwavering in his support even as damning evidence is revealed during her trial for war crimes. You ask yourself, did he so want to believe the woman he married was not capable of such evil that he accepted her assurances she didn’t do the things she was accused of?

Hermine’s first person narrative takes us through her early life to the annexation of Austria by Germany and the outbreak of the Second World War. She takes a job in a brewery, then in a munitions factory before learning from a German officer with whom she is besotted about a job in a newly built women’s prison. The prison is Ravensbruck. She’s told its purpose is to ‘re-educate criminals through hard work,’ an explanation she naively accepts. (She’ll later tell Russell she only took the job because it was better paid.) Initially, she is shocked by the violence meted out to prisoners. Soon, though, it’s she who is threatened with punishment if she doesn’t ‘toughen up’ and praised for physical violence against prisoners. Eventually, she willingly carries out the acts of brutality that earn her the nickname ‘the Mare’.

One of the most chilling thing about Hermine’s account is her increasing nonchalance about the things she is witnessing and doing. She complains, ‘It doesn’t matter how many prisoners we gas, more just keep on coming’, as if they are a logistical inconvenience rather than fellow human beings she’s consigning to a horrific death. Acts of unspeakable brutality are treated as commonplace or justified as ‘necessary’. And as time goes on she even takes pride in being recognised by her superiors for her ‘efficiency’. It’s disturbing to enter the mind of someone capable of such despicable acts but somehow you can’t look away. You want to understand how someone could get to the point where they lose all concept of humanity. The author makes you confront that question.

The brilliance of the book’s structure is that we get to see the contradictions between Hermine’s own account of her actions and motivations, and what she tells Russell about her wartime experiences: the omissions, the obfuscations, the downright lies. Even more so at her trial when she continues to dispute the evidence of multiple individuals who witnessed her cruelty although we know what they are saying is correct because she has already told us so herself.

It’s possible I overuse the word ‘thought-provoking’ in my book reviews but I genuinely think it’s justified here.

The Mare is an unflinching exploration of humanity’s capacity for violence.

In three words: Powerful, dark, compelling

Try something similar: The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis

About the Author

Angharad Hampshire was born in Manchester in 1972. She has worked as a producer for BBC Radio 4 and the World Service in London, honorary lecturer in journalism at the University of Hong Kong and regular contributor to the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong. She has a Doctor of Arts in Creative Writing from the University of Sydney. Angharad currently works as a research fellow at York St John University and teaches on the Creative Writing MA. She lives in York with her family.