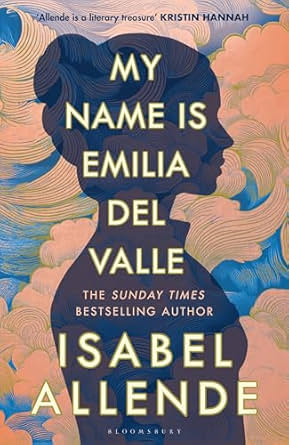

About the Book

Emilia del Valle was always destined for great things. Abandoned at birth by her Chilean aristocrat father, Emilia comes of age in nineteenth-century San Francisco as an independent and fiercely ambitious young woman, decades ahead of her time. She will do whatever it takes to pursue her life’s passion for writing, even if it means publishing under a man’s name.

When Emilia lands a position as a journalist for the Daily Examiner, her unwavering sense of adventure – and new-found determination to survive in her own name – leads her to seize the chance to cover a brewing civil war in Chile alongside another talented reporter.

But the assignment offers Emilia more than just an opportunity to prove herself as a writer. Before long she embarks on a treacherous, life-changing journey in a homeland she never knew, to uncover the truth about her father – and herself.

Format: Hardcover (304 pages) Publisher: Bloomsbury

Publication date: 6th May 2025 Genre: Historical Fiction

Find My Name is Emilia del Valle on Goodreads

Purchase My Name is Emilia del Valle from Bookshop.org [Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops]

My Review

My only previous experience of the work of Isabel Allende is A Long Petal of the Sea which I read back in 2022. I had been put off her books up to that point because she was known for her works of magic realism which is a genre I’ve been unable to get along with. However I really enjoyed A Long Petal of the Sea and when I saw this latest book was also a work of historical fiction I jumped at the chance to read it.

Essentially the author has created the fictional character of Emilia del Valle to enable her to explore a turbulent period of Chile’s history, namely the civil war that took place in that country in 1891 between the so-called ‘rebels’ who had the support of the Chilean Navy and supporters of the President José Manuel Balmaceda who controlled the Chilean Army.

I confess I found the early parts of the book a little slow because it’s quite a while before Emilia even arrives in Chile. However, by that time we’ve learned just what a determined young woman Emilia is, intent on pursuing a journalistic career despite the obstacles placed in her path and the sexism she experiences. ‘I recognize that it must be much easier to be a man, but I am not going to let that hold me back.’

Emilia even has to fight to have her articles published under her own name rather than a male pseudonym and the editor of the San Francisco newspaper she works for, The Daily Examiner, reluctantly agrees to send her to what is an active war zone only if accompanied by a male reporter, Eric Whelan. Even then she’s told to concentrate on producing ‘human interest’ stories rather than reporting from the front line. You won’t be surprised to learn Emilia ignores the latter instruction completely although we do get examples of her ability to describe the lives and motivations of people from every part of society in occasional transcripts of her newspaper articles.

Emilia’s journey from San Francisco to Chile is just one of the testing experiences she endures. When she arrives in Chile the reader is plunged into the complexity of the civil war with its rival factions. Whilst Whelan (whose first hand experiences we occasionally get) is embedded with the ‘rebel’ forces, Emilia uses her connections to get up close to the government side. The point where the two sides come together is where the book came alive for me. The brutality of war is really laid bare in the way the scenes of battle are described and, amazingly, Emilia finds herself right at the heart of it. ‘The deafening roar of bullets, cannon blasts, shouted orders, howls of pain, wails of dying men, the whinnying of terrified horses.’

Civil war not only divides countries, it divides people and families. Many combatants on both sides have no particular loyalty to the cause or desire to kill their fellow men and women. They often have no choice. And, as we discover, you definitely do not want to be on the losing side and experience the ruthless and bloody aftermath.

Emilia feels it is her mission to tell the stories of the ordinary men and women caught up in the conflict, in her words ‘to collect the dispersed fragments of those tales’. One of the most notable of these tales are those of the women known as ‘canteen girls’ whose task is to carry water and other supplies to men in the front line, even in the heat of battle.

Her experiences leave Emilia mentally – and physically – scarred, and wondering at mankind’s capacity for violence. ‘How is it possible that, from the dawn of their presence on earth, men have systematically set out to murder one another? What fatal madness do we carry in our soul?’ I suspect it’s a question many of us have thought about in recent times.

Emilia’s attempts to find her birth father form a secondary story line and one that makes up a less signficant element of the book than I’d envisaged from the blurb. However, it does provide the jumping-off point for the final part of the book which sees Emilia embark on an epic journey by land but first by sea. ‘Sea and more sea, short days and long nights, the sun winking out on the horizon, golden twilights, the moon gliding across the black sky, crimson sunrises, radiant noonday clarity, sepulchral clouds.’ It’s a journey that’s as much self-exploratory as geographical and gives the closing chapters a rather mystical air.

There were parts of My Name is Emilia del Valle that I found absolutely riveting and I enjoyed finding out more about the history of Chile and its culture. The author is known for creating strong female characters and Emilia is a brilliant example of this.

I received an advance reader copy courtesy of Bloomsbury via NetGalley.

In three words: Dramatic, immersive, authentic

Try something similar: The Map of Bones by Kate Mosse

About the Author

Isabel Allende, born in Peru and raised in Chile, is a novelist, feminist, and philanthropist. She is one of the most widely read authors in the world, having sold more than eighty million copies of her books across forty-two languages. She is the author of several bestselling and critically acclaimed books, including The Wind Knows My Name, Violeta, A Long Petal of the Sea, The House of the Spirits, Of Love and Shadows, Eva Luna, and Paula. In addition to her work as a writer, Isabel devotes much of her time to human rights causes. She has received fifteen honorary doctorates, been inducted into the California Hall of Fame, and received the PEN Center Lifetime Achievement Award and the Anisfield-Wolf Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2014, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, and in 2018, she received the Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters from the National Book Foundation. She lives in California with her husband and dogs.