About the Book

‘Truth, she thought. As terrible as death. But harder to find.’

America, fifteen years after the end of the Second World War. The winning Axis powers have divided their spoils: the Nazis control New York, while California is ruled by the Japanese.

But between these two states – locked in a cold war – lies a neutral buffer zone in which legendary author Hawthorne Abendsen is rumoured to live. Abendsen lives in fear of his life for he has written a book in which World War Two was won by the Allies . . .

Format: ebook (274 pages) Publisher: Penguin

Publication date: 2nd August 2012 [1962] Genre: Science Fiction

Find The Man in the High Castle on Goodreads

My Review

I was delighted when 1962 was chosen by Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings and Simon at Stuck in a Book as the year for this twice-yearly reading club because I’ve had The Man in the High Castle on my Kindle since October 2017 and this has given me the push I needed to read it.

In his excellent introduction to this Penguin Moderns Classics edition, Eric Brown describes Philip K. Dick as having been ‘obsessed with the idea that the universe was only apparently real, an illusion behind which the truth might dwell’. The author presents an alternate history – that the United States lost the Second World War – and has been divided into three states: the eastern seaboard ruled by Nazi Germany, the western seaboard by the Japanese and the third, the autonomous Rocky Mountain State which is in effect a demilitarized zone between the other two. Many high-ranking Nazis live on, including Heydrich, Goebbels and Bormann, although Hitler has gone mad and is confined to an asylum. As one character observes, ‘A psychotic world we live in. The madmen are in power’.

The book explores the consequences of the war’s outcome through the lives of a number of different characters including Juliana who works as a Judo instructor in the Rocky Mountain State, Juliana’s estranged husband Frank Frink, Robert Childan a trader in pre-war American artefacts and Nobusuke Tagomi, head of the Japanese trade mission in San Francisco.

Into this Dick inserts an ‘alternate’ alternate history, as many of the characters are reading a book entitled The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, the premise of which is that Germany and Japan were defeated. Its author is the ‘Man in the High Castle’ of the title but is he a visionary or a kind of amanuensis? In fact, at one point a character experiences a brief glimpse of the US of that ‘alternate’ alternate history, suggesting perhaps the existence of a parallel universe.

Another theme of the book is what constitutes the real as opposed to the fake, something that was central to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, but here is more concerned with objects than with humans. For example, Robert Childan sells historical artefacts to Japanese collectors some of which may in fact be reproductions. And when Frank Frink, disillusioned with producing such reproductions, starts a business creating original, handmade jewellery he is advised to have the pieces mass-produced and promoted as good luck charms.

Identity and status is another theme, especially in the area of the United States now under occupation by Japan. In one scene, Mr Tagomi attends a meeting taking with him an empty briefcase because he feels to go without it would give the appearance of being ‘a mere spectator’. In another Robert Childan worries how it will appear to others if he carries his own packages rather than using a slave. Cleverly, the author has Robert’s speech and internal dialogue mimic the rhythms of the Japanese occupiers to whom he is considered inferior.

I found the book fascinating and became immersed in the lives of the characters. My favourite was Mr Tagomi because of the extent to which we witness his moral conflicts. I’m afraid I did struggle with the frequent references to the Chinese divination text, the I Ching, on which many of the characters rely to determine what course they should take.

The Man in the High Castle is a chilling dystopia in which whole continents have been destroyed, their populations killed or consigned to servitude, in which slavery is once again legal and the few Jewish people who survived the Holocaust must hide their identities or face death. It’s a nightmare vision but one that sometimes feels uncomfortably close to present day events.

In three words: Thought-provoking, insightful, imaginative

Try something similar: Fatherland by Robert Harris

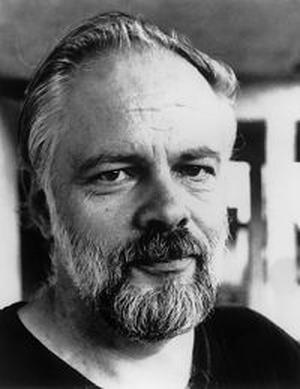

About the Author

Philip K. Dick was born in Chicago in 1928, but lived most of his life in California, briefly attending the University of California at Berkeley in 1947. Among the most prolific and eccentric of SF writers, Dick’s many novels and stories all blend a sharp and quirky imagination with a strong sense of the surreal.

By the time of his death in 1982 he had written over thirty science-fiction novels and 112 short stories. Notable titles amongst the novels include The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1965), Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968, later used as the basis for the film Blade Runner), Ubik (1969) and A Scanner Darkly (1977). The Man in the High Castle (1962), perhaps his most painstakingly constructed and chilling novel, won a Hugo Award in 1963.