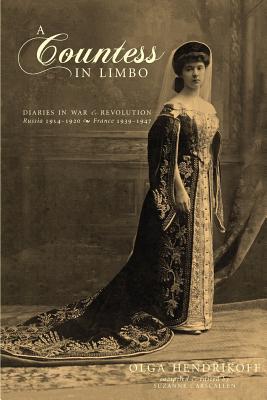

One remarkable woman’s experiences of living through turbulent times

About the Book

About the Book

Countess Olga “Lala” Hendrikoff was born into the Russian aristocracy, serving as lady-in-waiting to the empresses and enjoying a life of great privilege. But on the eve of her wedding in 1914 came the first rumours of an impending war—a war that would change her life forever and force her to flee her country as a stateless person with no country to call home. Her personal writings have been collected and translated by her great niece, Sue Carscallen, to form A Countess in Limbo: Diaries in War and Revolution.

Spanning two of the most turbulent times in modern history—World War I in Russia and World War II in Paris—Countess Hendrikoff’s journals demonstrate the uncertainty, horror, and hope of daily life in the midst of turmoil. Her razor-sharp insight, wit, and sense of humour create a fascinating eyewitness account of the Russian Revolution and the occupation and liberation of Paris.

Book Facts

- Format: ebook

- Publisher: Archway Publishing

- No. of pages: 337

- Publication date: 3rd November 2016

- Genre: Memoir, Non-Fiction, History

Purchase links*

Amazon

Barnes and Noble

Archway Publishing

*links provided for convenience, not as part of any affiliate programme

Find A Countess in Limbo on Goodreads

My Review

I found these journals absolutely fascinating and I was amazed how a woman could live through such upheaval, struggle, loss and privation and still provide such an objective commentary on events, managing to see the good – and bad – on both sides.

In the first section, the young Olga recounts some of her experiences living in Russia at the outbreak of World War I. There are touching scenes, such as when she and her mother witness the departure of her younger brother to join the army.

‘To the strains of martial music, the train, illuminated by the last rays of the setting sun, started pulling away from the platform and soon vanished in the evening darkness. With long-repressed tears flowing without measure, my mother and I stood on the platform for a few more minutes.’

Olga did not keep journals throughout her life – or at least, none remain – so there are gaps where only her great niece’s research can try to provide welcome answers. One such mystery is the circumstances around the ending of her marriage after only three years.

The sections of the book containing the journals Olga Hendrikoff kept during World War 2 – covering the onset of war, the occupation of France and its liberation – I found particularly compelling. Throughout there is a sense of incredulity that nations should so quickly repeat the mistakes of history.

‘Another war with Germany seems incredible to me when no-one has yet forgotten the last one.’

‘I often wake up in the morning thinking I have had a bad dream – the war, the departure of friends and relatives… The first few days after the war was declared, it was if I was stunned. I could not bring myself to believe that the country I live in is really at war.’

Olga documents the daily struggle to find food, fuel to keep warm and employment so that items only available on the thriving black market can be purchased. She vividly describes how the German advance into France provokes the desperate flight of people.

‘The route nationale is still clogged with refugees who make use of any means of locomotion: men on bicycles, women on foot pushing baby carriages, babies in wheelbarrows pulled like trailers by bicycles, mule- or horse-drawn carriages, strollers…in a word, anything on wheels, anything that rolls, has been mobilised for the exodus.’

The liberation of Paris brings no end to the food shortages, power cuts and daily struggle. It also brings something worse – reprisals against those deemed to have been collaborators.

‘In the troubled times we are going through, alas, the spirit of personal vengeance is naturally given free rein.’

Olga becomes one of hundreds of thousands stateless émigrés, in her case unable to return to Russia following the revolution and its transformation into the Soviet Union. However, she never loses her affection for her homeland, which she looks back on fondly.

‘Would it suddenly be possible to go back to your own country and see Russian forests again, the rivers you knew as a child, the landscapes you still hold in your heart?’

In the end, economic pressures force her to leave France and, since a return to Russia is impossible, she embarks for America where she spent the remainder of her long life.

Countess Hendrikoff was clearly a remarkable woman with wit, intelligence, resilience, compassion for others and a relentless determination to survive. It is wonderful that her journals survive in order that modern readers can share her experiences and her admirable outlook on life. There is so much more that I could mention about this book but I will simply urge you to read it for yourself. One final quotation, should you need further persuading:

‘All war seems absurd to me anyway. The victors often lose in the exchange, and the vanquished think only of revenge.’

A lesson we do not yet seem to have learned.

I received a review copy courtesy of the author and publishers, Archway Publishing, in return for an honest review.

In three words: Enthralling, moving, inspirational

Try something similar…The Past is Myself by Christabel Bielenberg

About the Authors

Olga Hendrikoff was born in 1892 in Voronezh, Russia, and attended the famous Smolny Institute. In 1914, she married Count Peter Hendrikoff just as World War I began. In the ensuing years, Hendrikoff lived in Constantinople, Rome, Paris, and Philadelphia. She spent her last 20 years in Calgary. She died in 1987.

Sue Carscallen spent 20 years with Olga Hendrikoff before her great aunt’s passing in 1987. Carscallen stumbled upon Hendrikoff’s diaries hidden in a trunk at her great aunt’s Calgary home. Over time she unraveled the mysteries hidden in the manuscripts, traveling to France and Russia to supplement her research into Hendrikoff’s life. Today, Carscallen resides in Calgary.

Sue Carscallen spent 20 years with Olga Hendrikoff before her great aunt’s passing in 1987. Carscallen stumbled upon Hendrikoff’s diaries hidden in a trunk at her great aunt’s Calgary home. Over time she unraveled the mysteries hidden in the manuscripts, traveling to France and Russia to supplement her research into Hendrikoff’s life. Today, Carscallen resides in Calgary.

Find out more…

Read a fascinating interview with Sue Carscallen about her great aunt, the discovery of her journals and how this book came into being.

Website: www.acountessinlimbo.com