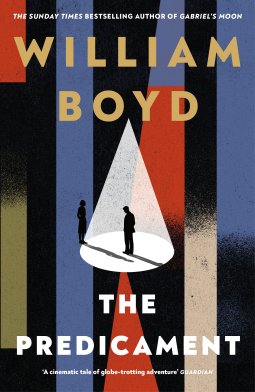

About the Book

Gabriel Dax, travel writer and accidental spy, is back in the shadows. Unable to resist the allure of his MI6 handler, Faith Green, he has returned to a life of secrets and subterfuge. Dax is sent to Guatemala under the guise of covering a tinderbox presidential election, where the ruthless decisions of the Mafia provoke pitch-black warfare in collusion with the CIA.

As political turmoil erupts, Gabriel’s reluctant involvement deepens. His escape plan leads him to West Berlin, where he uncovers a chilling realisation: there is a plot to assassinate magnetic young President John F. Kennedy. In a race against time, Gabriel must navigate deceit and danger, knowing that the stakes have never been higher . . .

Format: Hardcover (272 pages) Publisher: Viking

Publication date: 4th September 2025 Genre: Historical Fiction, Thriller

Find The Predicament on Goodreads

Purchase The Predicament from Bookshop.org [Disclosure: If you buy books linked to our site, we may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookshops]

My Review

Gabriel Dax is certainly in a predicament. He’s in thrall to Faith Green, the head of the MI6 section known as ‘the termite hunters’ charged with rooting out traitors within the service. He finds her alluring but something of an enigma. Indeed he refers to her as ‘the Sphinx of the Institute of Developmental Studies’, the cover name for her section.

Does she feel the same way about him? Sometimes he thinks the answer is yes, at other times he wonders if he’s just being manipulated because his travel writing provides useful cover for trips abroad and opens doors that might otherwise be closed. Such is the case when he’s sent to Guatamala to interview an influential presidential candidate. His last interview with a similar figure didn’t end well, and this time is no different.

So enmeshed in the secret world of espionage has Gabriel become that he’s found himself in the dubious position of posing as a double agent for the Russians, acting as decoy for a British triple agent. The only upside is the Russians are generous with money enabling him to move to the countryside in the hope of finding some peace and quiet to work on his latest book. Some hope…

Gabriel is someone you can’t help rooting for even though he often makes foolish blunders and lets his fascination with Faith lead him into all sorts of dangerous situations. Having said that, Faith is facing her own challenges just at the moment. To quote Shakespeare, ‘When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions’ because a problem Gabriel encountered on his previous mission, which he thought he’d put to bed permanently, resurfaces (literally), he’s being sued for plagiarism and his ex-girlfriend Lorraine is keen to rekindle their relationship. His only respite from his problems is his sessions with his therapist, Dr Katrina Haas.

The book has all the hallmarks of an espionage thriller with Gabriel forced to adopt the sort of spycraft you’d find in a John lé Carre novel, including how to lose someone trying to follow you. He’s also given a quick lesson in how to kill using only the contents of your pockets, such as a notebook or set of keys. The prospect of finding himself in a dangerous situation involving some very nasty people is never far away.

From Guatemala the action moves to West Berlin (don’t worry, there are connections) and sees Gabriel become involved in frantic attempts to disrupt a plot to assassinate President John F. Kennedy. You might be thinking, we all know JFK wasn’t assassinated in Berlin so where’s the tension? But of course Gabriel doesn’t know that. His frenzied efforts to spot a face in the crowd, a face only he has seen, and then the sudden realisation that everyone is on the wrong track is absolutely gripping even if it does have strong ‘The Day of the Jackal’ vibes.

The Predicament is a thoroughly enjoyable, stylish spy thriller with a great sense of time and place.

I received a review copy courtesy of Viking via NetGalley.

In three words: Intriguing, entertaining, well-crafted

Try something similar: The Day of the Jackal by Frederick Forsyth

About the Author

William Boyd was born in 1952 in Accra, Ghana, and grew up there and in Nigeria. He is the author of sixteen highly acclaimed, bestselling novels and five collections of stories. Any Human Heart was longlisted for the Booker Prize and adapted into a TV series with Channel 4. In 2005, Boyd was awarded the CBE. He is married and divides his time between London and south-west France. (Photo: Goodreads author page/Bio: Publisher author page)