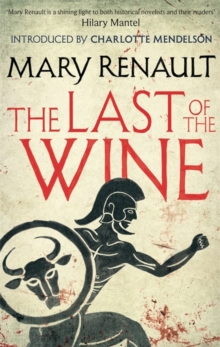

About the Book

Alexias, a young Athenian of good family, comes of age during the last phases of the Peloponnesian War. The adult world he enters is one in which the power and influence of his class have been undermined by the forces of war. Alexias finds himself drawn to the controversial teachings of Socrates, following him even though it at times endangers both his own life and his family’s place in society.

Among the great teacher’s followers Alexias meets Lysis, and the two youths become inseparable – together they wrestle in the palaestra, journey to the Olympic Games, and fight in the wars against Sparta. As their relationship develops against the background of famine, siege and civil conflict, Mary Renault expertly conveys the intricacies of classical Greek culture.

Format: ebook (371 pages) Publisher: Virago

Publication date: 6 August 2015 [1956] Genre: Historical Fiction, Modern Classics

Find The Last of the Wine on Goodreads

Purchase links*

Amazon UK | Hive (supporting UK bookshops)

*links provided for convenience not as part of an affiliate programme

My Review

The Last of the Wine was my book for the recent 1956 Club hosted by Simon at Stuck In A Book and Kaggsy at Kaggsy’s Bookish Ramblings. Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to finish reading the book or write my review during the event.

As soon as I started reading The Last of the Wine, two things struck me. Firstly, I realized I’d read it before, back in 2015. Secondly, that when I read The Flowers of Adonis by Rosemary Sutcliff a few months ago, the reason the story seemed so familiar is that the two books cover pretty much the same ground, namely the Peloponnesian War between Athens and Sparta in the period 431 to 405 BC. The difference is that, whereas Alkibiades is the main focus of The Flowers of Adonis (albeit his exploits are described by a series of different narrators), in The Last of the Wine he remains largely off-stage with events being seen from the point of view of Alexias, a young Athenian.

In her introduction to my Virago Modern Classics edition of The Last of the Wine, Charlotte Mendelson describes Mary Renault as “an Ancient Greek” because of her knowledge of the period and her ability to bring it to life. I agree entirely because the novel wears its historical research lightly, instead immersing the reader in the details of daily life, social and religious rituals. This means The Last of the Wine is more than just a history of the political and military events of that period, it’s the story of a deep and loving relationship between two young men, Alexias and Lysis. Those who enjoy action scenes won’t be disappointed either and there are parts for famous figures of Greek philosophy such as Socrates and Plato.

I was surprised to learn Renault was nearly fifty when she began writing The Last of the Wine and that, although it was her seventh novel, it was the first to be set in Ancient Greece. I must admit I’d always thought of Renault as a writer of exclusively historical fiction. Mendelson argues the timing was due to the parallels Renault saw between the South Africa in which she was living at the time and her desire to write a love story whose protagonists just happened to be homosexual and would not be “shamed, imprisoned or hounded to death”.

Renault’s insight when writing about love – and grief – is evident. “Then the pain of loss leaped out on me, like a knife in the night when one has been on one’s guard all day. The world grew hollow, a place of shadows…” Women barely figure in the book, except those offering sexual services or as wives needing protection. As Charlotte Mendelson notes, the men “have the best characters, the best bodies and best lines”.

In three words: Immersive, exciting, emotional

Try something similar: The Flowers of Adonis by Rosemary Sutcliff

Follow this blog via Bloglovin

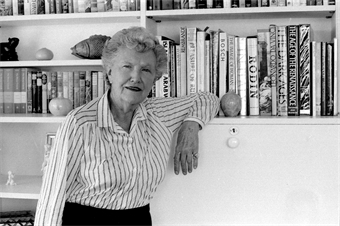

About the Author

Mary Renault (1905 – 1983) was best known for her historical novels set in Ancient Greece with their vivid fictional portrayals of Theseus, Socrates, Plato and Alexander the Great.

Born in London and educated at the University of Oxford, she trained as a nurse at Oxford’s Radcliffe Infirmary where she met her lifelong partner, fellow nurse Julie Mullard. After completing her training she wrote her first novel, Purposes of Love, in 1937. In 1948, after her novel North Face won a MGM prize worth $150,000, she and Mullard emigrated to South Africa.

It was in South Africa that Renault was able to write forthrightly about homosexual relationships for the first time – in her last contemporary novel, The Charioteer, published in 1953, and then in her first historical novel, 1956’s The Last of the Wine, the story of two young Athenians who study under Socrates and fight against Sparta. Both these books had male protagonists, as did all her later works that included homosexual themes. Her sympathetic treatment of love between men would win Renault a wide gay readership.

In 2006 Mary was the subject of a BBC4 documentary and her books, many of which remain in print on both sides of the Atlantic, are often sought after for radio and dramatic interpretation. In 2010, Fire From Heaven was shortlisted for the Lost Booker of 1970. (Bio credit: Curtis Brown)